Folk music

| Folk music | |

|---|---|

Béla Bartók recording peasant singers in Zobordarázs, Kingdom of Hungary, (now Nitra, Slovakia) 1907 | |

| Traditions | List of folk music traditions |

| Musicians | List of folk musicians |

| Instruments | Folk instruments |

| Other topics | |

Folk music is a music genre that includes traditional folk music and the contemporary genre that evolved from the former during the 20th-century folk revival. Some types of folk music may be called world music. Traditional folk music has been defined in several ways: as music transmitted orally, music with unknown composers, music that is played on traditional instruments, music about cultural or national identity, music that changes between generations (folk process), music associated with a people's folklore, or music performed by custom over a long period of time. It has been contrasted with commercial and classical styles. The term originated in the 19th century, but folk music extends beyond that.

Starting in the mid-20th century, a new form of popular folk music evolved from traditional folk music. This process and period is called the (second) folk revival and reached a zenith in the 1960s. This form of music is sometimes called contemporary folk music or folk revival music to distinguish it from earlier folk forms.[1] Smaller, similar revivals have occurred elsewhere in the world at other times, but the term folk music has typically not been applied to the new music created during those revivals. This type of folk music also includes fusion genres such as folk rock, folk metal, and others. While contemporary folk music is a genre generally distinct from traditional folk music, in U.S. English it shares the same name, and it often shares the same performers and venues as traditional folk music.

Traditional folk music

[edit]| Traditional folk music | |

|---|---|

| Stylistic origins | Traditional music |

| Cultural origins | Individual nations or regions |

| Derivative forms | |

| Subgenres | |

| Contemporary folk music (Western) Contemporary folk music (non-Western) (complete list) | |

| Fusion genres | |

| Other topics | |

Definition

[edit]The terms folk music, folk song, and folk dance are comparatively recent expressions. They are extensions of the term folklore, which was coined in 1846 by the English antiquarian William Thoms to describe "the traditions, customs, and superstitions of the uncultured classes".[2] The term further derives from the German expression Volk, in the sense of "the people as a whole" as applied to popular and national music by Johann Gottfried Herder and the German Romantics over half a century earlier.[3] Though it is understood that folk music is the music of the people, observers find a more precise definition to be elusive.[4][5] Some do not even agree that the term folk music should be used.[4] Folk music may tend to have certain characteristics[2] but it cannot clearly be differentiated in purely musical terms. One meaning often given is that of "old songs, with no known composers,"[6] another is that of music that has been submitted to an evolutionary "process of oral transmission... the fashioning and re-fashioning of the music by the community that give it its folk character."[7]

Such definitions depend upon "(cultural) processes rather than abstract musical types...", upon "continuity and oral transmission...seen as characterizing one side of a cultural dichotomy, the other side of which is found not only in the lower layers of feudal, capitalist and some oriental societies but also in 'primitive' societies and in parts of 'popular cultures'".[8] One widely used definition is simply "Folk music is what the people sing."[9]

For Scholes,[2] as well as for Cecil Sharp and Béla Bartók,[10] there was a sense of the music of the country as distinct from that of the town. Folk music was already, "...seen as the authentic expression of a way of life now past or about to disappear (or in some cases, to be preserved or somehow revived),"[11] particularly in "a community uninfluenced by art music"[7] and by commercial and printed song. Lloyd rejected this in favor of a simple distinction of economic class[10] yet for him, true folk music was, in Charles Seeger's words, "associated with a lower class"[12] in culturally and socially stratified societies. In these terms, folk music may be seen as part of a "schema comprising four musical types: 'primitive' or 'tribal'; 'elite' or 'art'; 'folk'; and 'popular'."[13]

Music in this genre is also often called traditional music. Although the term is usually only descriptive, in some cases people use it as the name of a genre. For example, the Grammy Award previously used the terms "traditional music" and "traditional folk" for folk music that is not contemporary folk music.[14] Folk music may include most indigenous music.[4]

Characteristics

[edit]

From a historical perspective, traditional folk music had these characteristics:[12]

- It was transmitted through an oral tradition. Before the 20th century, ordinary people were usually illiterate; they acquired songs by memorizing them. Primarily, this was not mediated by books or recorded or transmitted media. Singers may extend their repertoire using broadsheets or song books, but these secondary enhancements are of the same character as the primary songs experienced in the flesh.

- The music was often related to national culture. It was culturally particular; from a particular region or culture. In the context of an immigrant group, folk music acquires an extra dimension for social cohesion. It is particularly conspicuous in immigrant societies, where Greek Australians, Somali Americans, Punjabi Canadians, and others strive to emphasize their cultural identity. They learn songs and dances that originate in the countries their grandparents came from.

- They commemorate historical and personal events. On certain days of the year, including such holidays as Christmas, Easter, and May Day, particular songs celebrate the yearly cycle. Birthdays, weddings, and funerals may also be noted with songs, dances and special costumes. Religious festivals often have a folk music component. Choral music at these events brings children and non-professional singers to participate in a public arena, giving an emotional bonding that is unrelated to the aesthetic qualities of the music.

- The songs have been performed, by custom, over a long period of time, usually several generations.

As a side-effect, the following characteristics are sometimes present:

- There is no copyright on the songs. Hundreds of folk songs from the 19th century have known authors but have continued in oral tradition to the point where they are considered traditional for purposes of music publishing. This has become much less frequent since the 1940s. Today, almost every folk song that is recorded is credited with an arranger.

- Fusion of cultures: Because cultures interact and change over time, traditional songs evolving over time may incorporate and reflect influences from disparate cultures. The relevant factors may include instrumentation, tunings, voicings, phrasing, subject matter, and even production methods.

Tune

[edit]In folk music, a tune is a short instrumental piece, a melody, often with repeating sections, and usually played a number of times.[15] A collection of tunes with structural similarities is known as a tune-family. America's Musical Landscape says "the most common form for tunes in folk music is AABB, also known as binary form."[16][page needed]

In some traditions, tunes may be strung together in medleys or "sets."[17]

Origins

[edit]

Throughout most of human history, listening to recorded music was not possible.[18][19] Music was made by common people during both their work and leisure, as well as during religious activities. The work of economic production was often manual and communal.[20] Manual labor often included singing by the workers, which served several practical purposes.[21] It reduced the boredom of repetitive tasks, it kept the rhythm during synchronized pushes and pulls, and it set the pace of many activities such as planting, weeding, reaping, threshing, weaving, and milling. In leisure time, singing and playing musical instruments were common forms of entertainment and history-telling—even more common than today when electrically enabled technologies and widespread literacy make other forms of entertainment and information-sharing competitive.[22]

Some believe that folk music originated as art music that was changed and probably debased by oral transmission while reflecting the character of the society that produced it.[2] In many societies, especially preliterate ones, the cultural transmission of folk music requires learning by ear, although notation has evolved in some cultures.[23] Different cultures may have different notions concerning a division between "folk" music on the one hand and of "art" and "court" music on the other. In the proliferation of popular music genres, some traditional folk music became also referred to as "World music" or "Roots music".[24]

The English term "folklore", to describe traditional folk music and dance, entered the vocabulary of many continental European nations, each of which had its folk-song collectors and revivalists.[2] The distinction between "authentic" folk and national and popular song in general has always been loose, particularly in America and Germany[2] – for example, popular songwriters such as Stephen Foster could be termed "folk" in America.[2][25] The International Folk Music Council definition allows that the term can also apply to music that, "...has originated with an individual composer and has subsequently been absorbed into the unwritten, living tradition of a community. But the term does not cover a song, dance, or tune that has been taken over ready-made and remains unchanged."[26]

The post–World War II folk revival in America and in Britain started a new genre, Contemporary Folk Music, and brought an additional meaning to the term "folk music": newly composed songs, fixed in form and by known authors, which imitated some form of traditional music. The popularity of "contemporary folk" recordings caused the appearance of the category "Folk" in the Grammy Awards of 1959;[27] in 1970 the term was dropped in favor of "Best Ethnic or Traditional Recording (including Traditional Blues)",[28] while 1987 brought a distinction between "Best Traditional Folk Recording" and "Best Contemporary Folk Recording".[29] After that, they had a "Traditional music" category that subsequently evolved into others. The term "folk", by the start of the 21st century, could cover singer-songwriters, such as Donovan[30] from Scotland and American Bob Dylan,[31] who emerged in the 1960s and much more. This completed a process to where "folk music" no longer meant only traditional folk music.[6]

Subject matter

[edit]

Traditional folk music often includes sung words, although folk instrumental music occurs commonly in dance music traditions. Narrative verse looms large in the traditional folk music of many cultures.[32][33] This encompasses such forms as traditional epic poetry, much of which was meant originally for oral performance, sometimes accompanied by instruments.[34][35] Many epic poems of various cultures were pieced together from shorter pieces of traditional narrative verse, which explains their episodic structure, repetitive elements, and their frequent in medias res plot developments. Other forms of traditional narrative verse relate the outcomes of battles or lament tragedies or natural disasters.[36]

Sometimes, as in the triumphant Song of Deborah[37] found in the Biblical Book of Judges, these songs celebrate victory. Laments for lost battles and wars, and the lives lost in them, are equally prominent in many traditions; these laments keep alive the cause for which the battle was fought.[38][39] The narratives of traditional songs often also remember folk heroes such as John Henry[40][41] or Robin Hood.[42] Some traditional song narratives recall supernatural events or mysterious deaths.[43]

Hymns and other forms of religious music are often of traditional and unknown origin.[44] Western musical notation was originally created to preserve the lines of Gregorian chant, which before its invention was taught as an oral tradition in monastic communities.[45][46] Traditional songs such as Green grow the rushes, O present religious lore in a mnemonic form, as do Western Christmas carols and similar traditional songs.[47]

Work songs frequently feature call and response structures and are designed to enable the laborers who sing them to coordinate their efforts in accordance with the rhythms of the songs.[48] They are frequently, but not invariably, composed. In the American armed forces, a lively oral tradition preserves jody calls ("Duckworth chants") which are sung while soldiers are on the march.[49] Professional sailors made similar use of a large body of sea shanties.[50][51] Love poetry, often of a tragic or regretful nature, prominently figures in many folk traditions.[52] Nursery rhymes, children's songs and nonsense verse used to amuse or quiet children also are frequent subjects of traditional songs.[53]

Folk song transformations and variations

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2022) |

Music transmitted by word of mouth through a community, in time, develops many variants, since this transmission cannot produce word-for-word and note-for-note accuracy. In addition, folk singers may choose to modify the songs they hear.

For example, around 1970 the song Mullā Mohammed Jān spread from Herat to the rest of Afghanistan, and Iran where it was recorded. Due to its repetitive refrain and the predictability of the second half of each verse, it allowed for both its popularization, and for each singer to create their own version of the song without being overly-concerned for a melody or restrictive poetic rhythm.[54]

Because variants proliferate naturally, there is generally no "authoritative" version of song. Researchers in traditional songs have encountered countless versions of the Barbara Allen ballad throughout the English-speaking world, and these versions often differ greatly from each other. The original is not known; many versions can lay an equal claim to authenticity.

Influential folklorist Cecil Sharp felt that these competing variants of a traditional song would undergo a process of improvement akin to biological natural selection: only those new variants that were the most appealing to ordinary singers would be picked up by others and transmitted onward in time. Thus, over time we would expect each traditional song to become more aesthetically appealing, due to incremental community improvement.

Literary interest in the popular ballad form dates back at least to Thomas Percy and William Wordsworth. English Elizabethan and Stuart composers had often evolved their music from folk themes, the classical suite was based upon stylised folk-dances, and Joseph Haydn's use of folk melodies is noted. But the emergence of the term "folk" coincided with an "outburst of national feeling all over Europe" that was particularly strong at the edges of Europe, where national identity was most asserted. Nationalist composers emerged in Central Europe, Russia, Scandinavia, Spain and Britain: the music of Dvořák, Smetana, Grieg, Rimsky-Korsakov, Brahms, Liszt, de Falla, Wagner, Sibelius, Vaughan Williams, Bartók, and many others drew upon folk melodies.[citation needed]

Regional forms

[edit]

While the loss of traditional folk music in the face of the rise of popular music is a worldwide phenomenon,[55] it is not one occurring at a uniform rate throughout the world.[56] The process is most advanced "where industrialization and commercialisation of culture are most advanced"[57] but also occurs more gradually even in settings of lower technological advancement. However, the loss of traditional music is slowed in nations or regions where traditional folk music is a badge of cultural or national identity.[citation needed]

Early folk music, fieldwork and scholarship

[edit]Much of what is known about folk music prior to the development of audio recording technology in the 19th century comes from fieldwork and writings of scholars, collectors and proponents.[58]

19th-century Europe

[edit]Starting in the 19th century, academics and amateur scholars, taking note of the musical traditions being lost, initiated various efforts to preserve the music of the people.[59] One such effort was the collection by Francis James Child in the late 19th century of the texts of over three hundred ballads in the English and Scots traditions (called the Child Ballads), some of which predated the 16th century.[9]

Contemporaneously with Child, the Reverend Sabine Baring-Gould and later Cecil Sharp worked to preserve a great body of English rural traditional song, music and dance, under the aegis of what became and remains the English Folk Dance and Song Society (EFDSS).[60] Sharp campaigned with some success to have English traditional songs (in his own heavily edited and expurgated versions) to be taught to school children in hopes of reviving and prolonging the popularity of those songs.[61][62] Throughout the 1960s and early to mid-1970s, American scholar Bertrand Harris Bronson published an exhaustive four-volume collection of the then-known variations of both the texts and tunes associated with what came to be known as the Child Canon.[63] He also advanced some significant theories concerning the workings of oral-aural tradition.[64]

Similar activity was also under way in other countries. One of the most extensive was perhaps the work done in Riga by Krisjanis Barons, who between the years 1894 and 1915 published six volumes that included the texts of 217,996 Latvian folk songs, the Latvju dainas.[65] In Norway the work of collectors such as Ludvig Mathias Lindeman was extensively used by Edvard Grieg in his Lyric Pieces for piano and in other works, which became immensely popular.[66]

Around this time, composers of classical music developed a strong interest in collecting traditional songs, and a number of composers carried out their own field work on traditional music. These included Percy Grainger[67] and Ralph Vaughan Williams[68] in England and Béla Bartók[69] in Hungary. These composers, like many of their predecessors, both made arrangements of folk songs and incorporated traditional material into original classical compositions.[70][71]

North America

[edit]

The advent of audio recording technology provided folklorists with a revolutionary tool to preserve vanishing musical forms.[72] The earliest American folk music scholars were with the American Folklore Society (AFS), which emerged in the late 1800s.[73] Their studies expanded to include Native American music, but still treated folk music as a historical item preserved in isolated societies as well.[74] In North America, during the 1930s and 1940s, the Library of Congress worked through the offices of traditional music collectors Robert Winslow Gordon,[75] Alan Lomax[76][77][78] and others to capture as much North American field material as possible.[79] John Lomax (the father of Alan Lomax) was the first prominent scholar to study distinctly American folk music such as that of cowboys and southern blacks. His first major published work was in 1911, Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads.[80] and was arguably the most prominent US folk music scholar of his time, notably during the beginnings of the folk music revival in the 1930s and early 1940s. Cecil Sharp also worked in America, recording the traditional songs of the Appalachian Mountains in 1916–1918 in collaboration with Maud Karpeles and Olive Dame Campbell and is considered the first major scholar covering American folk music.[81] Campbell and Sharp are represented under other names by actors in the modern movie Songcatcher.[82]

One strong theme amongst folk scholars in the early decades of the 20th century was regionalism,[83] the analysis of the diversity of folk music (and related cultures) based on regions of the US rather than based on a given song's historical roots.[84][85] Later, a dynamic of class and circumstances was added to this.[86] The most prominent regionalists were literary figures with a particular interest in folklore.[87][88] Carl Sandburg often traveled the U.S. as a writer and a poet.[89] He also collected songs in his travels and, in 1927, published them in the book The American Songbag.[90] Rachel Donaldson, a historian who worked for Vanderbilt, later stated this about The American Songbird in her analysis of the folk music revival. "In his collections of folk songs, Sandburg added a class dynamic to popular understandings of American folk music. This was the final element of the foundation upon which the early folk music revivalists constructed their own view of Americanism. Sandburg's working-class Americans joined with the ethnically, racially, and regionally diverse citizens that other scholars, public intellectuals, and folklorists celebrated their own definitions of the American folk, definitions that the folk revivalists used in constructing their own understanding of American folk music, and an overarching American identity".[91]

Prior to the 1930s, the study of folk music was primarily the province of scholars and collectors. The 1930s saw the beginnings of larger scale themes, commonalities, and linkages in folk music developing in the populace and practitioners as well, often related to the Great Depression.[92] Regionalism and cultural pluralism grew as influences and themes. During this time folk music began to become enmeshed with political and social activism themes and movements.[92] Two related developments were the U.S. Communist Party's interest in folk music as a way to reach and influence Americans,[93] and politically active prominent folk musicians and scholars seeing communism as a possible better system, through the lens of the Great Depression.[94] Woody Guthrie exemplifies songwriters and artists with such an outlook.[95]

Folk music festivals proliferated during the 1930s.[96] President Franklin Roosevelt was a fan of folk music, hosted folk concerts at the White House, and often patronized folk festivals.[97] One prominent festival was Sarah Gertrude Knott's National Folk Festival, established in St. Louis, Missouri in 1934.[98] Under the sponsorship of the Washington Post, the festival was held in Washington, DC at Constitution Hall from 1937 to 1942.[99] The folk music movement, festivals, and the wartime effort were seen as forces for social goods such as democracy, cultural pluralism, and the removal of culture and race-based barriers.[100]

The American folk music revivalists of the 1930s approached folk music in different ways.[101] Three primary schools of thought emerged: "Traditionalists" (e.g. Sarah Gertrude Knott and John Lomax) emphasized the preservation of songs as artifacts of deceased cultures. "Functional" folklorists (e.g. Botkin and Alan Lomax) maintained that songs only retain relevance when used by those cultures which retain the traditions which birthed those songs. "Left-wing" folk revivalists (e.g. Charles Seeger and Lawrence Gellert) emphasized music's role "in 'people's' struggles for social and political rights".[101] By the end of the 1930s these and others had turned American folk music into a social movement.[101]

Sometimes folk musicians became scholars and advocates themselves. For example, Jean Ritchie (1922–2015) was the youngest child of a large family from Viper, Kentucky that had preserved many of the old Appalachian traditional songs.[102] Ritchie, living in a time when the Appalachians had opened up to outside influence, was university educated and ultimately moved to New York City, where she made a number of classic recordings of the family repertoire and published an important compilation of these songs.[103]

In January 2012, the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress, with the Association for Cultural Equity, announced that they would release Lomax's vast archive of 1946 and later recording in digital form. Lomax spent the last 20 years of his life working on an Interactive Multimedia educational computer project he called the Global Jukebox, which included 5,000 hours of sound recordings, 400,000 feet of film, 3,000 videotapes, and 5,000 photographs.[104] As of March 2012, this has been accomplished. Approximately 17,400 of Lomax's recordings from 1946 and later have been made available free online.[105][106] This material from Alan Lomax's independent archive, begun in 1946, which has been digitized and offered by the Association for Cultural Equity, is "distinct from the thousands of earlier recordings on acetate and aluminum discs he made from 1933 to 1942 under the auspices of the Library of Congress. This earlier collection—which includes the famous Jelly Roll Morton, Woody Guthrie, Lead Belly, and Muddy Waters sessions, as well as Lomax's prodigious collections made in Haiti and Eastern Kentucky (1937) — is the provenance of the American Folklife Center"[105] at the library of Congress.

National and regional forms

[edit]Africa

[edit]

Africa is a vast continent[107] and its regions and nations have distinct musical traditions.[108][109] The music of North Africa for the most part has a different history from Sub-Saharan African music traditions.[110]

The music and dance forms of the African diaspora, including African American music and many Caribbean genres like soca, calypso and Zouk; and Latin American music genres like the samba, Cuban rumba, salsa; and other clave (rhythm)-based genres, were founded to varying degrees on the music of enslaved Africans, which has in turn influenced African popular music.[111][112]

Asia

[edit]

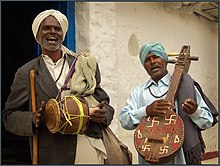

Many Asian civilizations distinguish between art/court/classical styles and "folk" music.[113][114] For example, the late Alam Lohar is an example of a South Asian singer who was classified as a folk singer.[115]

Khunung Eshei/Khuland Eshei is an ancient folk song from India, a country of Asia, of Meiteis of Manipur, that is an example of Asian folk music, and how they put it into its own genre.[116]

Folk music of China

[edit]Archaeological discoveries date Chinese folk music back 7000 years;[117] it is largely based on the pentatonic scale.[118]

Han traditional weddings and funerals usually include a form of oboe called a suona,[119] and apercussive ensembles called a chuigushou.[120] Ensembles consisting of mouth organs (sheng), shawms (suona), flutes (dizi) and percussion instruments (especially yunluo gongs) are popular in northern villages;[121] their music is descended from the imperial temple music of Beijing, Xi'an, Wutai shan and Tianjin. Xi'an drum music, consisting of wind and percussive instruments,[122] is popular around Xi'an, and has received some commercial popularity outside of China.[123] Another important instrument is the sheng, a type of Chinese pipe, an ancient instrument that is ancestor of all Western free reed instruments, such as the accordion.[124] Parades led by Western-type brass bands are common, often competing in volume with a shawm/chuigushou band.

In southern Fujian and Taiwan, Nanyin or Nanguan is a genre of traditional ballads.[125] They are sung by a woman accompanied by a xiao and a pipa, as well as other traditional instruments.[126] The music is generally sorrowful and typically deals with love-stricken people.[127][128] Further south, in Shantou, Hakka and Chaozhou, zheng ensembles are popular.[129] Sizhu ensembles use flutes and bowed or plucked string instruments to make harmonious and melodious music that has become popular in the West among some listeners.[130] These are popular in Nanjing and Hangzhou, as well as elsewhere along the southern Yangtze area.[131] Jiangnan Sizhu (silk and bamboo music from Jiangnan) is a style of instrumental music, often played by amateur musicians in tea houses in Shanghai.[132] Guangdong Music or Cantonese Music is instrumental music from Guangzhou and surrounding areas.[133] The music from this region influenced Yueju (Cantonese Opera) music,[134] which would later grow popular during the self-described "Golden Age" of China under the PRC.[135]

Folk songs have been recorded since ancient times in China. The term Yuefu was used for a broad range of songs such as ballads, laments, folk songs, love songs, and songs performed at court.[136] China is a vast country, with a multiplicity of linguistic and geographic regions. Folk songs are categorized by geographic region, language type, ethnicity, social function (e.g. work song, ritual song, courting song) and musical type. Modern anthologies collected by Chinese folklorists distinguish between traditional songs, revolutionary songs, and newly invented songs.[137] The songs of northwest China are known as "flower songs" (hua'er), a reference to beautiful women, while in the past they were notorious for their erotic content.[138] The village "mountain songs" (shan'ge) of Jiangsu province were also well known for their amorous themes.[139][140] Other regional song traditions include the "strummed lyrics" (tanci) of the Lower Yangtze Delta, the Cantonese Wooden Fish tradition (muyu or muk-yu) and the Drum Songs (guci) of north China.[141]

In the twenty-first century many cherished Chinese folk songs have been inscribed in the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.[142] In the process, songs once seen as vulgar are now being reconstructed as romantic courtship songs.[143] Regional song competitions, popular in many communities, have promoted professional folk singing as a career, with some individual folk singers having gained national prominence.[144]

Traditional folk music of Sri Lanka

[edit]The art, music and dance of Sri Lanka derive from the elements of nature, and have been enjoyed and developed in the Buddhist environment.[145] The music is of several types and uses only a few types of instruments.[146] The folk songs and poems were used in social gatherings to work together. The Indian influenced classical music has grown to be unique.[147][148][149][150] The traditional drama, music and songs of Sinhala Light Music are typically Sri Lankan.[151] The temple paintings and carvings feature birds, elephants, wild animals, flowers, and trees, and the Traditional 18 Dances display the dancing of birds and animals.[152] For example:

- Mayura Wannama – The dance of the peacock[153][154]

- Hanuma Wannama – The dance of the monkey[155]

- Gajaga Wannama – The dance of the elephant

Musical types include:

- Local drama music includes Kolam[156] and Nadagam types.[157] Kolam music is based on low country tunes primarily to accompany mask dance in exorcism rituals.[158][159] It is considered less developed/evolved, true to the folk tradition and a preserving of a more ancient artform.[160] It is limited to approximately 3–4 notes and is used by the ordinary people for pleasure and entertainment.[161]

- Nadagam music is a more developed form of drama influenced from South Indian street drama which was introduced by some south Indian artists. Phillippu Singho from Negombo in 1824 performed "Harishchandra Nadagama" in Hnguranketha which was originally written in the Telingu language. Later "Maname",[162] "Sanda kinduru"[163] and others were introduced. Don Bastian of Dehiwala introduced Noorthy firstly by looking at Indian dramas and then John de Silva developed it as did Ramayanaya in 1886.[164]

- Sinhala light music is currently the most popular type of music in Sri Lanka and enriched with the influence of folk music, kolam music, nadagam music, noorthy music, film music, classical music, Western music, and others.[165] Some artists visited India to learn music and later started introducing light music. Ananda Samarakone was the pioneer of this[166][167] and also composed the national anthem.[168]

The classical Sinhalese orchestra consists of five categories of instruments, but among the percussion instruments, the drum is essential for dance.[169] The vibrant beat of the rhythm of the drums form the basic of the dance.[170] The dancers' feet bounce off the floor and they leap and swirl in patterns that reflect the complex rhythms of the drum beat. This drum beat may seem simple on the first hearing but it takes a long time to master the intricate rhythms and variations, which the drummer sometimes can bring to a crescendo of intensity. There are six common types of drums falling within 3 styles (one-faced, two-faced, and flat-faced):[171][172]

- The typical Sinhala Dance is identified as the Kandyan dance and the Gatabera drum is indispensable to this dance.[173]

- Yak-bera is the demon drum or the drum used in low country dance in which the dancers wear masks and perform devil dancing, which has become a highly developed form of art.[174]

- The Daula is a barrel-shaped drum, and it was used as a companion drum with a Thammattama in the past, to keep strict time with the beat.[175]

- The Thammattama is a flat, two-faced drum. The drummer strikes the drum on the two surfaces on top with sticks, unlike the others where you drum on the sides. This is a companion drum to the aforementioned Dawula.[176]

- A small double-headed hand drum is used to accompany songs. It is primarily heard in the poetry dances like vannam.[clarification needed]

- The Rabana is a flat-faced circular drum and comes in several sizes.[177] The large Rabana - called the Banku Rabana - has to be placed on the floor like a circular short-legged table and several people (traditionally women) can sit around it and beat on it with both hands.[178] This is used in festivals such as the Sinhalese New Year and ceremonies such as weddings.[179] The resounding beat of the Rabana symbolizes the joyous moods of the occasion. The small Rabana is a form of mobile drum beat since the player carries it wherever the person goes.[180]

Other instruments include:

- The Thalampata – 2 small cymbals joined by a string.[181]

- The wind section, is dominated by an instrument akin to the clarinet.[clarification needed] This is not normally used for dances. This is important to note because the Sinhalese dance is not set to music as the western world knows it; rhythm is king.

- The flutes of metal such as silver & brass produce shrill music to accompany Kandyan Dances, while the plaintive strains of music of the reed flute may pierce the air in devil-dancing. The conch-shell (Hakgediya) is another form of a natural instrument, and the player blows it to announce the opening of ceremonies of grandeur.[182]

- The Ravanahatha (ravanhatta, rawanhattha, ravanastron or ravana hasta veena) is a bowed fiddle that was once popular in Western India.[183][184] It is believed to have originated among the Hela civilisation of Sri Lanka in the time of King Ravana.[185] The bowl is made of cut coconut shell, the mouth of which is covered with goat hide. A dandi, made of bamboo, is attached to this shell.[185] The principal strings are two: one of steel and the other of a set of horsehair. The long bow has jingle bells[186][187]

Australia

[edit]Indigenous Australian music includes the music of Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islanders, who are collectively called Indigenous Australians;[188] it incorporates a variety of distinctive traditional music styles practiced by Indigenous Australian peoples, as well as a range of contemporary musical styles of and fusion with European traditions as interpreted and performed by indigenous Australian artists.[189] Music has formed an integral part of the social, cultural and ceremonial observances of these peoples, down through the millennia of their individual and collective histories to the present day.[190][191] The traditional forms include many aspects of performance and musical instruments unique to particular regions or Indigenous Australian groups.[192] Equal elements of musical tradition are common through much of the Australian continent, and even beyond.[193] The culture of the Torres Strait Islanders is related to that of adjacent parts of New Guinea and so their music is also related. Music is a vital part of Indigenous Australians' cultural maintenance.[194]

Folk song traditions were taken to Australia by early settlers from England, Scotland and Ireland and gained particular foothold in the rural outback.[195][196] The rhyming songs, poems and tales written in the form of bush ballads often relate to the itinerant and rebellious spirit of Australia in The Bush, and the authors and performers are often referred to as bush bards.[197] The 19th century was the golden age of bush ballads.[198] Several collectors have catalogued the songs including John Meredith whose recording in the 1950s became the basis of the collection in the National Library of Australia.[197]

The songs tell personal stories of life in the wide open country of Australia.[199][200] Typical subjects include mining, raising and droving cattle, sheep shearing, wanderings, war stories, the 1891 Australian shearers' strike, class conflicts between the landless working class and the squatters (landowners), and outlaws such as Ned Kelly, as well as love interests and more modern fare such as trucking.[201] The most famous bush ballad is "Waltzing Matilda", which has been called "the unofficial national anthem of Australia".[202]

Europe

[edit]

Celtic traditional music

[edit]Celtic music is a term used by artists, record companies, music stores and music magazines to describe a broad grouping of musical genres that evolved out of the folk musical traditions of the Celtic peoples.[203] These traditions include Irish, Scottish, Manx, Cornish, Welsh, and Breton traditions.[204] Asturian and Galician music is often included, though there is no significant research showing that this has any close musical relationship.[205][206] Brittany's Folk revival began in the 1950s with the "bagadoù" and the "kan-ha-diskan" before growing to world fame through Alan Stivell's work since the mid-1960s.[207]

In Ireland, The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem (although its members were all Irish-born, the group became famous while based in New York's Greenwich Village[208]), The Dubliners,[209] Clannad,[210] Planxty,[211] The Chieftains,[212][213] The Pogues,[214] The Corrs,[215] The Irish Rovers,[216] and a variety of other folk bands have done much over the past few decades to revitalise and re-popularise Irish traditional music.[217] These bands were rooted, to a greater or lesser extent, in a tradition of Irish music and benefited from the efforts of artists such as Seamus Ennis and Peter Kennedy.[207]

In Scotland, The Corries,[218] Silly Wizard,[219][220] Capercaillie,[221] Runrig,[222] Jackie Leven,[223] Julie Fowlis,[224] Karine Polwart,[225] Alasdair Roberts,[226][227] Dick Gaughan,[228] Wolfstone,[229] Boys of the Lough,[230] and The Silencers[231] have kept Scottish folk vibrant and fresh by mixing traditional Scottish and Gaelic folk songs with more contemporary genres.[232] These artists have also been commercially successful in continental Europe and North America.[233] There is an emerging wealth of talent in the Scottish traditional music scene, with bands such as Mànran,[234] Skipinnish,[235] Barluath[236] and Breabach[237] and solo artists such as Patsy Reid,[238] Robyn Stapleton[239] and Mischa MacPherson[240] gaining a lot of success in recent years.[241]

Central and Eastern Europe

[edit]During the Eastern Bloc era, national folk dancing was actively promoted by the state.[242] Dance troupes from Russia and Poland toured non-communist Europe from about 1937 to 1990.[243] The Red Army Choir recorded many albums, becoming the most popular military band.[244] Eastern Europe is also the origin of the Jewish Klezmer tradition.[245]

The polka is a central European dance and also a genre of dance music familiar throughout Europe and the Americas. It originated in the middle of the 19th century in Bohemia.[246] Polka is still a popular genre of folk music in many European countries and is performed by folk artists in Poland, Latvia, Lithuania, Czech Republic, Netherlands, Croatia, Slovenia, Germany, Hungary, Austria, Switzerland, Italy, Ukraine, Belarus, Russia and Slovakia.[247] Local varieties of this dance are also found in the Nordic countries, United Kingdom, Republic of Ireland, Latin America (especially Mexico), and in the United States.

German Volkslieder perpetuated by Liederhandschriften manuscripts like Carmina Burana[248] date back to medieval Minnesang and Meistersinger traditions.[249] Those folk songs revived in the late 18th century period of German Romanticism,[250] first promoted by Johann Gottfried Herder[251][252] and other advocates of the Enlightenment,[253] later compiled by Achim von Arnim[254] and Clemens Brentano (Des Knaben Wunderhorn)[255] as well as by Ludwig Uhland.[256]

The Volksmusik and folk dances genre, especially in the Alpine regions of Bavaria, Austria, Switzerland (Kuhreihen) and South Tyrol, up to today has lingered in rustic communities against the backdrop of industrialisation[257]—Low German shanties or the Wienerlied[258] (Schrammelmusik) being notable exceptions. Slovene folk music in Upper Carniola and Styria also originated from the Alpine traditions, like the prolific Lojze Slak Ensemble.[259] Traditional Volksmusik is not to be confused with commercial Volkstümliche Musik, which is a derivation of that.[260]

The Hungarian group Muzsikás played numerous American tours[261] and participated in the Hollywood movie The English Patient[262] while the singer Márta Sebestyén worked with the band Deep Forest.[263] The Hungarian táncház movement, started in the 1970s, involves strong cooperation between musicology experts and enthusiastic amateurs.[264] However, traditional Hungarian folk music and folk culture barely survived in some rural areas of Hungary, and it has also begun to disappear among the ethnic Hungarians in Transylvania. The táncház movement revived broader folk traditions of music, dance, and costume together and created a new kind of music club.[265] The movement spread to ethnic Hungarian communities elsewhere in the world.[265]

Balkan music

[edit]

Balkan folk music was influenced by the mingling of Balkan ethnic groups in the period of the Ottoman Empire.[266] It comprises the music of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Greece, Montenegro, Serbia, Romania, North Macedonia, Albania, some of the historical states of Yugoslavia or Serbia and Montenegro and geographical regions such as Thrace.[267] Some music is characterised by complex rhythm.[268]

A notable act is the Mystery of the Bulgarian Voices, which won the Grammy Award for Best Traditional Folk Recording at the 32nd annual ceremony.[269][270]

An important part of the whole Balkan folk music is the music of the local Romani ethnic minority, which is called tallava and brass band music.[271][272]

Nordic folk music

[edit]

Nordic folk music includes a number of traditions in Northern European, especially Scandinavian, countries. The Nordic countries are generally taken to include Iceland, Norway, Finland, Sweden, Denmark and Greenland.[273] Sometimes it is taken to include the Baltic countries of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania.[274]

The many regions of the Nordic countries share certain traditions, many of which have diverged significantly, like Psalmodicon of Denmark, Sweden, and Norway.[275] It is possible to group together the Baltic states (or, sometimes, only Estonia) and parts of northwest Russia as sharing cultural similarities,[276] although the relationship has gone cold in recent years.[277] Contrast with Norway, Sweden, Denmark and the Atlantic islands of Iceland and the Faroe Islands, which share virtually no similarities of that kind. Greenland's Inuit culture has its own unique musical traditions.[278] Finland shares many cultural similarities with both the Baltic nations and the Scandinavian nations. The Sami of Sweden, Norway, Finland and Russia have their own unique culture, with ties to the neighboring cultures.[279]

Swedish folk music is a genre of music based largely on folkloric collection work that began in the early 19th century in Sweden.[280] The primary instrument of Swedish folk music is the fiddle.[281] Another common instrument, unique to Swedish traditions, is the nyckelharpa.[282] Most Swedish instrumental folk music is dance music; the signature music and dance form within Swedish folk music is the polska.[283] Vocal and instrumental traditions in Sweden have tended to share tunes historically, though they have been performed separately.[284] Beginning with the folk music revival of the 1970s, vocalists and instrumentalists have also begun to perform together in folk music ensembles.

Latin America

[edit]The folk music of the Americas consists of the encounter and union of three main musical types: European traditional music, traditional music of the American natives, and tribal African music that arrived with slaves from that continent.

The particular case of Latin and South American music points to Andean music[285] among other native musical styles (such as Caribbean[286] and pampean), Iberian music of Spain and Portugal, and generally speaking African tribal music, the three of which fused together evolving in differentiated musical forms in Central and South America.

Andean music comes from the region of the Quechuas, Aymaras, and other peoples that inhabit the general area of the Inca Empire prior to European contact.[287] It includes folklore music of parts of Bolivia, Ecuador,[288] Chile, Colombia, Peru and Venezuela. Andean music is popular to different degrees across Latin America, having its core public in rural areas and among indigenous populations. The Nueva Canción movement of the 1970s revived the genre across Latin America and brought it to places where it was unknown or forgotten.

Nueva canción (Spanish for 'new song') is a movement and genre within Latin American and Iberian folk music, folk-inspired music, and socially committed music. In some respects its development and role is similar to the second folk music revival in North America. This includes evolution of this new genre from traditional folk music, essentially contemporary folk music except that that English genre term is not commonly applied to it. Nueva cancion is recognized as having played a powerful role in the social upheavals in Portugal, Spain and Latin America during the 1970s and 1980s.

Nueva cancion first surfaced during the 1960s as "The Chilean New Song" in Chile. The musical style emerged shortly afterwards in Spain and areas of Latin America where it came to be known under similar names. Nueva canción renewed traditional Latin American folk music, and with its political lyrics it was soon associated with revolutionary movements, the Latin American New Left, Liberation Theology, hippie and human rights movements. It would gain great popularity throughout Latin America, and it is regarded as a precursor to Rock en español.

Cueca is a family of musical styles and associated dances from Chile, Bolivia and Peru.

Trova and Son are styles of traditional Cuban music originating in the province of Oriente that includes influences from Spanish song and dance, such as Bolero and contradanza as well as Afro-Cuban rhythm and percussion elements.

Moda de viola is the name designated to Brazilian folk music. It is often performed with a 6-string nylon acoustic guitar, but the most traditional instrument is the viola caipira. The songs basically detailed the difficulties of life of those who work in the country. The themes are usually associated with the land, animals, folklore, impossible love and separation. Although there are some upbeat songs, most of them are nostalgic and melancholic.

North America

[edit]Canada

[edit]

Canada's traditional folk music is particularly diverse.[289] Even prior to liberalizing its immigration laws in the 1960s, Canada was ethnically diverse with dozens of different Indigenous and European groups present. In terms of music, academics do not speak of a Canadian tradition, but rather ethnic traditions (Acadian music, Irish-Canadian music, Blackfoot music, Innu music, Inuit music, Métis fiddle, etc.) and later in Eastern Canada regional traditions (Newfoundland music, Cape Breton fiddling, Quebecois music, etc.)

Traditional folk music of European origin has been present in Canada since the arrival of the first French and British settlers in the 16th and 17th centuries....They fished the coastal waters and farmed the shores of what became Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, and the St Lawrence River valley of Quebec.

The fur trade and its voyageurs brought this farther north and west into Canada; later lumbering operations and lumberjacks continued this process.

Agrarian settlement in eastern and southern Ontario and western Quebec in the early 19th century established a favorable milieu for the survival of many Anglo-Canadian folksongs and broadside ballads from Great Britain and the US. Despite massive industrialization, folk music traditions have persisted in many areas until today. In the north of Ontario, a large Franco-Ontarian population kept folk music of French origin alive.

Populous Acadian communities in the Atlantic provinces contributed their song variants to the huge corpus of folk music of French origin centred in the province of Quebec. A rich source of Anglo-Canadian folk music can be found in the Atlantic region, especially Newfoundland. Completing this mosaic of musical folklore is the Gaelic music of Scottish settlements, particularly in Cape Breton, and the hundreds of Irish songs whose presence in eastern Canada dates from the Irish famine of the 1840s, which forced the large migrations of Irish to North America.[289]

"Knowledge of the history of Canada", wrote Isabelle Mills in 1974, "is essential in understanding the mosaic of Canadian folk song. Part of this mosaic is supplied by the folk songs of Canada brought by European and Anglo-Saxon settlers to the new land."[12] She describes how the French colony at Québec brought French immigrants, followed before long by waves of immigrants from Great Britain, Germany, and other European countries, all bringing music from their homelands, some of which survives into the present day. Ethnographer and folklorist Marius Barbeau estimated that well over ten thousand French folk songs and their variants had been collected in Canada. Many of the older ones had by then died out in France.

Music as professionalized paid entertainment grew relatively slowly in Canada, especially remote rural areas, through the 19th and early 20th centuries. While in urban music clubs of the dance hall/vaudeville variety became popular, followed by jazz, rural Canada remained mostly a land of traditional music. Yet when American radio networks began broadcasting into Canada in the 1920s and 1930s, the audience for Canadian traditional music progressively declined in favour of American Nashville-style country music and urban styles like jazz. The Americanization of Canadian music led the Canadian Radio League to lobby for a national public broadcaster in the 1930s, eventually leading to the creation of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) in 1936. The CBC promoted Canadian music, including traditional music, on its radio and later television services, but the mid-century craze for all things "modern" led to the decline of folk music relative to rock and pop. Canada was however influenced by the folk music revival of the 1960s, when local venues such as the Montreal Folk Workshop, and other folk clubs and coffee houses across the country, became crucibles for emerging songwriters and performers as well as for interchange with artists visiting from abroad.

United States

[edit]American traditional music is also called roots music. Roots music is a broad category of music including bluegrass, country music, gospel, old time music, jug bands, Appalachian folk, blues, Cajun and Native American music. The music is considered American either because it is native to the United States or because it developed there, out of foreign origins, to such a degree that it struck musicologists as something distinctly new. It is considered "roots music" because it served as the basis of music later developed in the United States, including rock and roll, contemporary folk music, rhythm and blues, and jazz. Some of these genres are considered to be traditional folk music.

- Cajun music, an emblematic music of Louisiana, is rooted in the ballads of the French-speaking Acadians of Canada. Cajun music is often mentioned in tandem with the Creole-based, Cajun-influenced zydeco form, both of Acadiana origin. These French Louisiana sounds have influenced American popular music for many decades, especially country music, and have influenced pop culture through mass media, such as television commercials.

- Appalachian music is the traditional music of the region of Appalachia in the Eastern United States. It derives from various European and African influences, including English ballads, Irish and Scottish traditional music (especially fiddle music), hymns, and African-American blues. First recorded in the 1920s, Appalachian musicians were a key influence on the early development of Old-time music, country music, and bluegrass, and were an important part of the American folk music revival. Instruments typically used to perform Appalachian music include the banjo, American fiddle, fretted dulcimer, and guitar.[290] Early recorded Appalachian musicians include Fiddlin' John Carson, Henry Whitter, Bascom Lamar Lunsford, the Carter Family, Clarence Ashley, Frank Proffitt, and Dock Boggs, all of whom were initially recorded in the 1920s and 1930s. Several Appalachian musicians obtained renown during the folk revival of the 1950s and 1960s, including Jean Ritchie, Roscoe Holcomb, Ola Belle Reed, Lily May Ledford, and Doc Watson. Country and bluegrass artists such as Loretta Lynn, Roy Acuff, Dolly Parton, Earl Scruggs, Chet Atkins, and Don Reno were heavily influenced by traditional Appalachian music.[290] Artists such as Bob Dylan, Dave Van Ronk, Jerry Garcia, and Bruce Springsteen have performed Appalachian songs or rewritten versions of Appalachian songs.

- The Carter Family was a traditional American folk music group that recorded between 1927 and 1956. Their music had a profound impact on bluegrass, country, Southern gospel, pop and rock musicians. They were the first vocal group to become country music stars; a beginning of the divergence of country music from traditional folk music. Their recordings of such songs as "Wabash Cannonball" (1932), "Will the Circle Be Unbroken" (1935), "Wildwood Flower" (1928), and "Keep On the Sunny Side" (1928) made them country standards.[291]

- Oklahoma and southern US plains: Before recorded history American Indians in this area used songs and instrumentation; music and dance remain the core of ceremonial and social activities.[292] "Stomp dance" remains at its core, a call and response form; instrumentation is provided by rattles or shackles worn on the legs of women.[292] "Other southeastern nations have their own complexes of sacred and social songs, including those for animal dances and friendship dances, and songs that accompany stickball games. Central to the music of the southern Plains Indians is the drum, which has been called the heartbeat of Plains Indian music. Most of that genre can be traced back to activities of hunting and warfare, upon which plains culture was based."[292] The drum is central to the music of the southern plains Indians. During the reservation period, they used music to relieve boredom. Neighbors gathered, exchanged and created songs and dances; this is a part of the roots of the modern intertribal powwow. Another common instrument is the courting flute.[292]

- African-American folk music in the area has roots in slavery and emancipation. Sacred music—a capella and instrumentally-accompanied—is at the heart of the tradition. Early spirituals framed Christian beliefs within native practices and were heavily influenced by the music and rhythms of Africa."[292] Spirituals are prominent, and often use a call and response pattern.[292] "Gospel developed after the Civil War (1861–1865). It relied on biblical text for much of its direction, and the use of metaphors and imagery was common. Gospel is a "joyful noise", sometimes accompanied by instrumentation and almost always punctuated by hand clapping, toe tapping, and body movement."[292] "Shape-note or Sacred Harp singing developed in the early 19th century as a way for itinerant singing instructors to teach church songs in rural communities. They taught using song books in which musical notations of tones were represented by geometric shapes that were designed to associate a shape with its pitch. Sacred harp singing became popular in many Oklahoma rural communities, regardless of ethnicity."[292] Later the blues tradition developed, with roots in and parallels to sacred music.[292] Then jazz developed, born from a "blend of ragtime, gospel, and blues"[292]

- Anglo-Scots-Irish music traditions gained a place in Oklahoma after the Land Run of 1889. Because of its size and portability, the fiddle was the core of early Oklahoma Anglo music, but other instruments such as the guitar, mandolin, banjo, and steel guitar were added later. Various Oklahoma music traditions trace their roots to the British Isles, including cowboy ballads, western swing, and contemporary country and western."[292] Mexican immigrants began to reach Oklahoma in the 1870s, bringing beautiful canciones and corridos love songs, waltzes, and ballads along with them. Like American Indian communities, each rite of passage in Hispanic communities is accompanied by traditional music. The acoustic guitar, string bass, and violin provide the basic instrumentation for Mexican music, with maracas, flute, horns, or sometimes accordion filling out the sound.[292] Other Europeans (such as Bohemians and Germans) settled in the late 19th century. Their social activities centered on community halls, "where local musicians played polkas and waltzes on the accordion, piano, and brass instruments".[292] Later, Asians contributed to the musical mix. "Ancient music and dance traditions from the temples and courts of China, India, and Indonesia are preserved in Asian communities throughout the state, and popular song genres are continually layered on to these classical music forms"[292]

Folk music revivals

[edit]"It's self-perpetuating, regenerative. It's what you'd call a perennial American song. I don't think it needs a revival, resuscitation. It lives and flourishes. It really just needs people who are 18 years old to get exposed to it. But it will go on with or without them. The folk song is more powerful than anything on the radio, than anything that's released...It's that distillation of the voices that goes on for a long, long time, and that's what makes them strong."[293]

"Folk music revival" refers to either a period of renewed interest in traditional folk music, or to an event or period which transforms it; the latter usually includes a social activism component. A prominent example of the former is the British folk revival of approximately 1890–1920. The most prominent and influential example of the latter (to the extent that it is usually called "the folk music revival") is the folk revival of the mid 20th century, centered in the English-speaking world which gave birth to contemporary folk music.[294] See the "Contemporary folk music" article for a description of this revival.

One earlier revival influenced western classical music. Such composers as Percy Grainger, Ralph Vaughan Williams, and Béla Bartók made field recordings or transcriptions of folk singers and musicians.

In Spain, Isaac Albéniz (1860–1909) produced piano works reflect his Spanish heritage, including the Suite Iberia (1906–1909). Enrique Granados (1867–1918) composed zarzuela, Spanish light opera, and Danzas Españolas – Spanish Dances. Manuel de Falla (1876–1946) became interested in the cante jondo of Andalusian flamenco, the influence of which can be strongly felt in many of his works, which include Nights in the Gardens of Spain and Siete canciones populares españolas ("Seven Spanish Folksongs", for voice and piano). Composers such as Fernando Sor and Francisco Tarrega established the guitar as Spain's national instrument. Modern Spanish folk artists abound (Mil i Maria, Russian Red, et al.) modernizing while respecting the traditions of their forebears.

Flamenco grew in popularity through the 20th century, as did northern styles such as the Celtic music of Galicia. French classical composers, from Bizet to Ravel, also drew upon Spanish themes, and distinctive Spanish genres became universally recognized.

Folk music revivals or roots revivals also encompass a range of phenomena around the world where there is a renewed interest in traditional music. This is often by the young, often in the traditional music of their own country, and often included new incorporation of social awareness, causes, and evolutions of new music in the same style. Nueva canción, a similar evolution of a new form of socially committed music occurred in several Spanish-speaking countries.

Contemporary folk music

[edit]Festivals

[edit]United States

[edit]It is sometimes claimed that the earliest United States folk music festival was the Mountain Dance and Folk Festival,[295][296] 1928, in Asheville, North Carolina, founded by Bascom Lamar Lunsford.[297] The National Folk Festival (USA) is an itinerant folk festival in the United States.[298] Since 1934, it has been run by the National Council for the Traditional Arts (NCTA) and has been presented in 26 communities around the nation.[299] After leaving some of these communities, the National Folk Festival has spun off several locally run folk festivals in its wake including the Lowell Folk Festival,[300] the Richmond Folk Festival,[301] the American Folk Festival[302] and, most recently, the Montana Folk Festival.[303]

The Newport Folk Festival is an annual folk festival held near Newport, Rhode Island.[304] It ran most years from 1959 to 1970 and from 1985 to the present, with an attendance of approximately 10,000 people each year.[305]

The four-day Philadelphia Folk Festival began in 1962.[306] It is sponsored by the non-profit Philadelphia Folksong Society.[307] The event hosts contemporary and traditional artists in genres including World/Fusion, Celtic, Singer-Songwriter, Folk Rock, Country, Klezmer, and Dance.[308][309] It is held annually on the third weekend in August.[310] The event now hosts approximately 12,000 visitors, presenting bands on 6 stages.[311]

The Feast of the Hunters' Moon in Indiana draws approximately 60,000 visitors per year.[312]

United Kingdom

[edit]Sidmouth Festival began in 1954,[313] and Cambridge Folk Festival began in 1965.[314] The Cambridge Folk Festival in Cambridge, England is noted for having a very wide definition of who can be invited as folk musicians.[315] The "club tents" allow attendees to discover large numbers of unknown artists, who, for ten or 15 minutes each, present their work to the festival audience.[316]

Australia

[edit]The National Folk Festival is Australia's premier folk festival event and is attended by over 50,000 people.[317][318] The Woodford Folk Festival and Port Fairy Folk Festival are similarly amongst Australia's largest major annual events, attracting top international folk performers as well as many local artists.[319][320]

Canada

[edit]Stan Rogers is a lasting fixture of the Canadian folk festival Summerfolk, held annually in Owen Sound, Ontario, where the main stage and amphitheater are dedicated as the "Stan Rogers Memorial Canopy".[321] The festival is firmly fixed in tradition, with Rogers' song "The Mary Ellen Carter" being sung by all involved, including the audience and a medley of acts at the festival.[322][323] The Canmore Folk Music Festival is Alberta's longest running folk music festival.[324]

There are multitudes of folk festivals across Canada. Canso, Nova Scotia, has hosted the Stan Rogers Folk Festival the last weekend of July each year since 1997. The town of Wolfville hosts the Deep Roots Music Festival in September of each year. The Celtic Colours Celtic music festival is held each fall around the time that tree leaves are changing their colours, on Cape Breton Island, with venues across the island. Lunenburg, Nova Scotia has hosted the Lunenburg Folk Harbour Festival since 1986.

Other

[edit]Urkult Näsåker, Ångermanland held August each year is purportedly Sweden's largest world-music festival.[325]

See also

[edit]- Contemporary folk music

- Anthology of American Folk Music

- Canadian Folk Music Awards

- Country music

- Folk process

- List of classical and art music traditions

- List of folk festivals

- Roud Folk Song Index

- The Voice of the People anthology of UK folk songs

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Ruehl, Kim. "Folk Music". About.com definition. Archived from the original on November 22, 2016. Retrieved August 18, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g Percy Scholes, The Oxford Companion to Music, OUP 1977, article "Folk Song".

- ^ Lloyd, A.L. (1969). Folk Song in England. Panther Arts. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-586-02716-5.

- ^ a b c The Never-Ending Revival by Michael F. Scully University of Illinois Press Urbana and Chicago 2008 ISBN 978-0-252-03333-9

- ^ Middleton, Richard, Studying Popular Music, Philadelphia: Open University Press (1990/2002). ISBN 978-0-335-15275-9, p. 127.

- ^ a b Ronald D. Cohen Folk music: the basics (CRC Press, 2006), pp. 1–2.

- ^ a b International Folk Music Council definition (1954/5), given in Lloyd (1969) and Scholes (1977).

- ^ Charles Seeger (1980), citing the approach of Redfield (1947) and Dundes (1965), quoted in Middleton (1990) p. 127.

- ^ a b Donaldson, 2011 p. 13

- ^ a b A. L. Lloyd, Folk Song in England, Panther Arts, 1969, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Middleton, Richard 1990, p. 127. Studying Popular Music. Milton Keynes; Philadelphia: Open University Press. ISBN 978-0-335-15276-6, 0-335-15275-9

- ^ a b c Mills, Isabelle (1974). "The Heart of the Folk Song". Canadian Journal for Traditional Music. 2.

- ^ Charles Seeger (1980) quoted in Middleton (1990) p. 127.

- ^ "Explanation For Category Restructuring". GRAMMY.com. April 5, 2011. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ Harbron, Rob. "Folk Music: A resource for creative music-making Key Stages 3 & 4" (PDF). media.efdss.org. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ Crawford, Richard (1993). The American musical landscape. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-92545-8. OCLC 44954569.

- ^ Harbron, Rob. "Folk Dance Tune Sets" (PDF). media.efdss.org. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ Day, Timothy (2000). A century of recorded music : listening to musical history. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09401-5. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ "How listening to music has changed - CBBC Newsround". BBC. April 21, 2019. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ "Work in the Late 19th Century | Rise of Industrial America, 1876-1900 | U.S. History Primary Source Timeline | Classroom Materials at the Library of Congress | Library of Congress". Library of Congress. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ Wolterstroff, Nicholas. "Work Songs | The Yale ISM Review". ismreview.yale.edu. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ "To Hear Your Banjo Play, Alan Lomax's 1947 Documentary narrated by Pete Seeger". YouTube. June 14, 2007. Archived from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved December 29, 2012.

- ^ Harris, Christina (September 21, 2021). "What is Folk Music? The History of English and American Traditional Music". IOWALUM. Archived from the original on October 17, 2021. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ "Traditional and Ethnic | Musical Styles | Articles and Essays | The Library of Congress Celebrates the Songs of America | Digital Collections | Library of Congress". Library of Congress. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ A.L.Lloyd, Folk Song in England, Panther Arts, 1969

- ^ Quoted by both Scholes (1977) and Lloyd (1969).

- ^ "2nd Annual GRAMMY Awards". GRAMMY.com. November 28, 2017. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ "13th Annual GRAMMY Awards". GRAMMY.com. November 28, 2017. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ "30th Annual GRAMMY Awards". GRAMMY.com. November 28, 2017. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ "The Scottish Psychedelic Folk singer and songwriter Donovan turns 75 today". popexpresso.com. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ Kooper, Al. "Bob Dylan | Biography, Songs, Albums, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ Saunders, Gemma (November 6, 2020). "How to Write a Folk Song | Writing Folk Music - OpenMic". Open Mic UK. Archived from the original on October 29, 2021. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ "Traditional Ballads | Traditional and Ethnic | Musical Styles | Articles and Essays | The Library of Congress Celebrates the Songs of America | Digital Collections | Library of Congress". Library of Congress. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ Reynolds, Dwight (1995). Heroic Poets, Poetic Heroes. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-3174-6. JSTOR 10.7591/j.ctt207g77s. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ "World Epics |". edblogs.columbia.edu. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ Michael Meyer (2005). The Bedford Introduction to Literature. Bedford: St. Martin's Press. pp. 21–28. ISBN 978-0-312-41242-5.

- ^ "How Old Is the Song of Deborah?". www.bibleodyssey.org. Archived from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- ^ "Class Notes: How History Influences Music". www.yourclassical.org. August 19, 2014. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ "That's Why We're Marching: World War II and the American Folksong Movement". folkways.si.edu. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ Parks, Abby (August 1, 2013). "John Henry: Hero of American Folklore". Folk Renaissance. Archived from the original on October 26, 2021. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ "CONTENTdm". digitalcollections.uark.edu. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ House, Wallace. "Robin Hood Ballads". folkways.si.edu. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ "Fairies, both good and evil, in Irish traditional music and song". www.ucd.ie. January 28, 2013. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ Hawn, C Michael. "History of Hymns: 'We've Come This Far by Faith'". Discipleship Ministries. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ KWASNIEWSKI, Peter. "A brief history of Gregorian chant from King David to the present". www.catholiceducation.org. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ "A GUIDE TO GREGORIAN NOTATION" (PDF). gregorian-chant-hymns.com. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ Watson, Natalie (September 16, 2013). "Green Grow The Rushes, Ho! An English Folksong". Wonderful Things Heritage. Retrieved October 11, 2021.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Pekar, Sandy; Whittaker, Judie. "African American Work Songs and Hollers". voices.pitt.edu. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ "Who is Jody Anyway??". Military Cadence. October 5, 2014. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ Moreland, Catherine. "Sea Shanty Songs: A Deep Dive Into the Life of a Sailor". utilitarian.net. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ "SEA SHANTIES AND SAILORS' SONGS: A PRELIMINARY GUIDE TO RECORDINGS IN THE ARCHIVE OF FOLK CULTURE (The American Folklife Center, Library of Congress)". www.loc.gov. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ "The Folk Song Tradition in Wales". National Library of Wales Blog. March 6, 2020. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ "Nursery Rhymes (English Folk Music) - IMSLP: Free Sheet Music PDF Download". imslp.org. Archived from the original on October 27, 2021. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ Sakata, Hiromi Lorraine (1983). Music in the Mind: The Concept of Music and Musician in Afghanistan (1st ed.). Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press. p. 145. ISBN 9780873382656.

- ^ Bayard, Samuel P. (1955). "Decline and "Revival" of Anglo-American Folk Music". Midwest Folklore. 5 (2). Indiana University Press: 69–77. JSTOR 4317508. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ "The Decline of Folk Traditions in Modern Societies". www.humanitiesweb.org. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ "Celtic Harp Sheet Music - About Traditional Music". November 13, 2007. Archived from the original on November 13, 2007. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ Nettl, Bruno. "Folk Music". Encyclopedia Britannica. Encyclopedia Britannica, inc. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ "Folk Music Preservation". www.musicedmagic.com. Archived from the original on September 23, 2021. Retrieved October 12, 2021.

- ^ Pratt, S. R. S. (1965). "The English Folk Dance and Song Society". Journal of the Folklore Institute. 2 (3): 294–299. doi:10.2307/3814148. ISSN 0015-5934. JSTOR 3814148. Retrieved October 12, 2021.

- ^ "Cecil James Sharp Collection (at English Folk Dance & Song Society, London)". Vwml. Archived from the original on October 24, 2021. Retrieved October 12, 2021.

- ^ "English Folk-Songs For Schools - online book - Contents Page". www.traditionalmusic.co.uk. Retrieved October 12, 2021.

- ^ Bronson, Bertrand Harris (2015). The Traditional Tunes of the Child Ballads, Volume 4. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-6752-3. Retrieved October 12, 2021.

- ^ Knighten, Merrell Audy Jr. (1975). Chaucer 's "Troilus and Criseyde": Some Implications of the Oral Mode. Louisiana State University. pp. 1, 115. Retrieved October 12, 2021.

- ^ "Letonika.lv. Enciklopēdijas - Latvijas kultūras kanons. Latvju dainas". www.letonika.lv. Retrieved October 12, 2021.

- ^ AMBROSIN, Marco; RUSCHE, Eva Maria (2021). EDVARD GRIEG ALFEDANS (PDF). p. 1.

- ^ "Percy Grainger Folk Song Collection". www.vwml.org. Retrieved October 12, 2021.

- ^ "Ralph Vaughan Williams Folk Song Collection (at the British Library)". www.vwml.org. Retrieved October 12, 2021.

- ^ Appold, Juliette (September 20, 2018). "Béla Bartók and the Importance of Folk Music | NLS Music Notes". blogs.loc.gov. Retrieved October 12, 2021.

- ^ "Nineteenth-Century Classical Music". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved October 12, 2021.

- ^ "How Do Classical Composers Use Folk Music? | WQXR Editorial". WQXR. Retrieved October 12, 2021.

- ^ "Outreach Ethnomusicology - The Effect of Record Production Techniques in Mediating Recordings of Traditional Irish Music". www.o-em.org. Retrieved October 13, 2021.

- ^ Bell, Michael J. (1973). "William Wells Newell and the Foundation of American Folklore Scholarship". Journal of the Folklore Institute. 10 (1/2): 7–21. doi:10.2307/3813877. ISSN 0015-5934. JSTOR 3813877. Retrieved October 13, 2021.

- ^ Donaldson, 2011, pp. 22–23

- ^ "Folk-songs of America the Robert Winslow Gordon collection, 1922-1932". LOC. Retrieved October 13, 2021.

- ^ "Alan Lomax Collection, Manuscripts, Ideas". LOC. Retrieved October 13, 2021.

- ^ "Alan Lomax Collection, Manuscripts, General". LOC. Retrieved October 13, 2021.

- ^ "About this Collection | John A. Lomax and Alan Lomax Papers | Digital Collections | Library of Congress". The Library of Congress. Retrieved October 13, 2021.

- ^ Frisbie, Charlotte; Cutting, Jennifer. "American Folk Music and Folklore Recordings: A Selected List 1989 (American Folklife Center, Library of Congress)". LOC. Retrieved October 13, 2021.

- ^ Donaldson, 2011, pp. 24–26

- ^ Donaldson, 2011 p. 20

- ^ Williams, Elizabeth (March 29, 2015). "Songcatchers: Collecting "Lost" Ballads with Olive Dame Campbell and Cecil Sharp". ASA Annual Conference. Retrieved October 13, 2021.

- ^ "American Roots Music : Into the Classroom - Historical Background". PBS. Archived from the original on October 23, 2021. Retrieved October 13, 2021.

- ^ Foster, Kathryn A. "Regionalism on Purpose" (PDF). Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. Retrieved October 13, 2021.

- ^ "Regionalism". OxfordBibliographies. Retrieved October 13, 2021.

- ^ Donaldson, 2011, pp. 32–37

- ^ "Cultural Analysis, Volume 6, 2007: Burgundian Regionalism and French Republican Commercial Culture at the 1937 Paris International Exposition / Philip Whalen". Open Computing Facility at UC Berkeley.

- ^ Hufford, Mary. "Folklore 650" (PDF). Sas.upenn. Retrieved October 13, 2021.

- ^ Foundation, Poetry (October 12, 2021). "Carl Sandburg". Poetry Foundation.

- ^ "Digging the Depths of The American Songbag – Rare Book and Manuscript Library – U of I Library". www.library.illinois.edu. Retrieved October 13, 2021.

- ^ Donaldson, 2011, p. 37

- ^ a b Donaldson, 2011, pp. 39–55

- ^ Donaldson, 2011, pp. 72–74

- ^ Donaldson, 2011, pp. 67–70

- ^ Leonard, Aaron. "Woody Guthrie's Communism and "This Land Is Your Land" | History News Network". hnn.us. Retrieved October 13, 2021.

- ^ Donaldson, 2011, pp. 44–52

- ^ Donaldson, 2011, pp. 42–43

- ^ Michael Ann Williams, Staging Tradition: John Lair and Sarah Gertrude Knott (University of Illinois Press, 2006) p. 13

- ^ Donaldson, 2011, pp. 103–04

- ^ Donaldson, 2011, pp. 105–07

- ^ a b c Donaldson, 2011, p. 87

- ^ Fox, Margalit (June 2, 2015). "Jean Ritchie, Lyrical Voice of Appalachia, Dies at 92". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 1, 2022. Retrieved October 13, 2021.

- ^ "Folk Songs Of The Southern Appalachians As Sung By Jean Ritchie (PDF) eBOOK". Handleybaptist. Archived from the original on October 26, 2021. Retrieved October 13, 2021.

- ^ "The Premiere of the Global Jukebox". Archived February 2, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Radio interview with Don Fleming by John Hockenberry on PRI's The Takeaway.

- ^ a b "Association for Cultural Equity's main overview and search page for Lomax's 1946-on recordings". archive.culturalequity.org. Retrieved September 8, 2021.

- ^ "Alan Lomax's Massive Archive Goes Online : The Record". NPR.org. NPR. March 28, 2012. Retrieved December 29, 2012.

- ^ "Overview". World Bank. Retrieved October 13, 2021.